The Hereford Times has launched an appeal for a memorial to wartime scientist Alan Blumlein, who died in a plane crash in Herefordshire in 1942. His work played a key role in our victory of Nazi Germany. Garth Lawson reveals more about Blumlein's links to his more lauded colleague Sir Bernard Lovell

THE H2S airborne radar on which Blumlein was working on is indelibly linked to the distinguished radio astronomer, Sir Bernard Lovell.

Lovell had cut his teeth by working for Martin Ryle of the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, in the cosmic ray research team at the University of Manchester.

In 1939, Ryle joined JA Ratcliffe’s ionospheric research group at the Cavendish Laboratory.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Ratcliffe joined the Air Ministry Research Establishment, later to become the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) at Malvern with their associated flying unit (TFU) at RAF Defford. The focus of their activity was to develop radar systems to be installed in aircraft, among them the one which was codenamed H2S, 'home sweet home', and Ryle followed Ratcliffe to the TRE in May 1940.

This set the scene for Ratcliffe to supervise the activities of Ryle, Antony Hewish and Bernard Lovell, who would all become the leaders of UK radio astronomy.

The development of radar during the Second World War had an important consequence for these pioneers – the extraordinary research efforts to design powerful radio transmitters, sensitive receivers and improved radio antennae resulted in new technologies which were to be exploited by radio astronomers, all of whom came from a background in radar.

The three main groups were led by Ryle at the Cavendish, Joseph Pawsey at Sydney and Bernard Lovell.

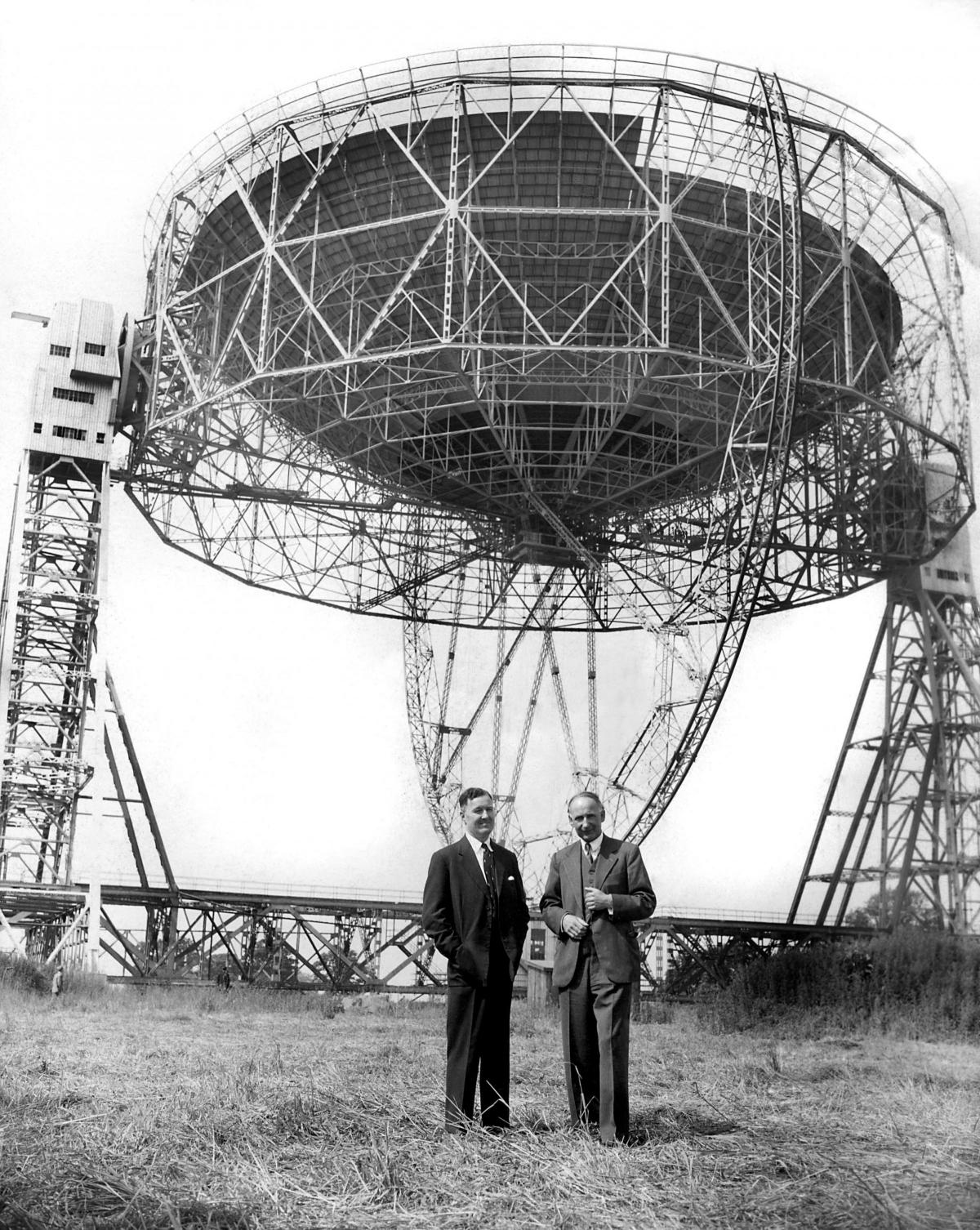

So, when EMI began a collaboration with TRE at Defford near Malvern, devising radar equipment to help British bombers find their targets at night, Blumlein was joining a team led by Lovell, who would go on to make his name not only as a radio astronomer but also creator of the Jodrell Bank telescope.

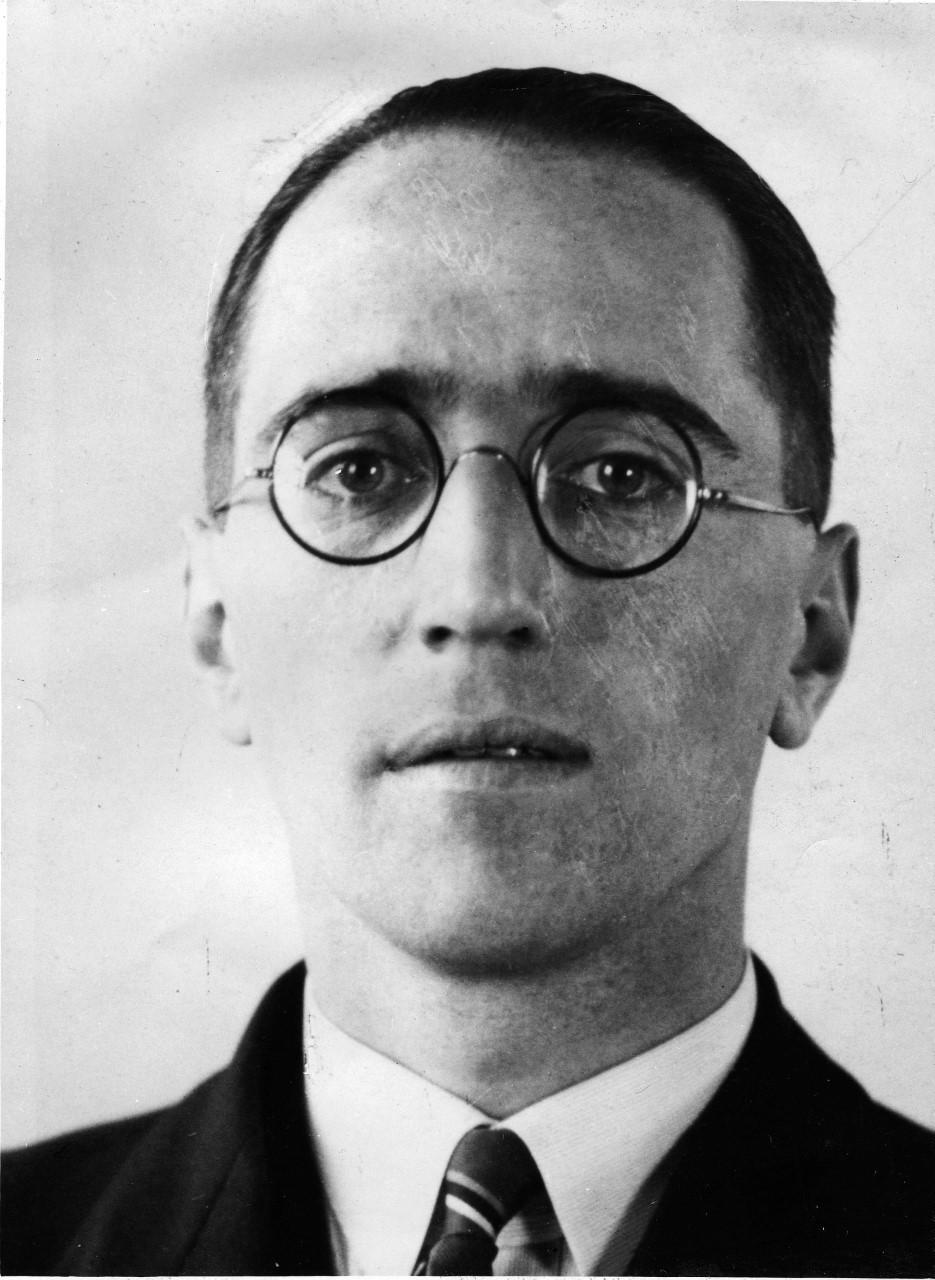

Followers of the Hereford Times Blumlein Memorial Appeal will know that, in devising the H2S system and while testing the radar on June 7, 1942, 38-year-old Blumlein died alongside his close colleagues from EMI, Cecil Oswald Browne and Frank Blythen, three from TRE and five from TFU.

It was the UK’s worst ever military test flight tragedy.

Less well known is that Bernard Lovell, who was later knighted for his work founding and running the Jodrell Bank Observatory, had flown on the plane the day before and reputedly gave up his seat on the flight that fateful day.

"I thought that was the end of it," Lovell reflected. "We were summoned by Churchill to the cabinet room and he said that he must have two squadrons with the equipment by October. I remember meekly saying, 'Prime Minister, we’ve lost our only equipment and I’m afraid this is not possible,' and he became very angry and said, “Young man, you’ve lost one aircraft. Don’t you realise we lost 30 over Cologne last night?”

Lovell described the loss of Blumlein as a ‘national disaster,’ but luckily the crucial magnetron for the radar was retrieved from the crash site and the system went into production at the end of January 1943.

The Blumlein family has welcomed the appeal to mark his memory.

“He was one of the greatest electronics engineers ever to have lived, contributing not just to the world of audio but to early telecommunications, the television system adopted by the BBC in 1936 and, during World War II, in the development of the crucial H2S airborne radar system that contributed greatly to Britain winning the war,” says Alan Blumlein, who shares his grandfather’s name.

“Recognition of my grandfather’s work has been sporadic outside the audio recording industry.

“In 1977, the London GLC mounted a blue plaque on the last house that he lived in at 37 The Ridings in Ealing, London, and in 2008, a building at RAF Defford was named the Alan Blumlein Building by Princess Anne.

- Contribute to our appeal for a permanent memorial to Alan Blumlein in Herefordshire. Visit www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/glawson

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here