TODAY marks 55 years since the Aberfan disaster.

At 9.15am this morning, Wales fell silent to remember those who lost their lives in the disaster.

Disaster struck the South Wales village on October 21 1966.

More than 150,000 tonnes of coal waste, loosened by persistent rain, slid down a hillside, killing 116 children and 28 adults.

Pit villages in South Wales were all too familiar with the danger that mining brought. Until the Aberfan disaster, it was the men underground who faced this peril.

October 21, 1966, saw the youngest and most vulnerable pay the highest price for the coal hewn from the ground.

In more recent times, the events of October 21, 1966 were played out in a poignant, moving episode of popular Netflix show The Crown.

The day of the disaster was the last day of school before Pantglas Junior School broke up for half-term. The mood would have been light and the children giddy with anticipation.

Ten-year-old Dilys Pope was excited about the coming half-term break. "We were in standard four and laughing and talking among ourselves waiting for our teacher to call the register” she recalled.

"We heard a noise and we heard all stuff flying around. The desks were falling over and the children were shouting and screaming. We couldn't see anything but then the dust began to go away.

"My leg got caught in a desk and could not move and my arm was hurting.

"The children were lying all over the place. The teacher Mr Williams, was also on the floor. He managed to free himself and he smashed the window in the door with a stone.

"I climbed out and went round through the hall and then out through the window. I opened the classroom window and some of the children came out that way. The teacher got some of the children out and he told us to go home."

The spoil from the Merthyr Vale colliery was dumped on the hillsides above Aberfan. Many villages across South Wales had great piles of coal waste which loomed above them. The tip which sat nearly a mile from Aberfan was piled on top of a stream. Its base was loosened by autumn rain and it swept thousands of tons of slurry swiftly and silently down the hill towards the unsuspecting villagers below.

It first took a farmhouse with it and flattened houses before it tore through Pantglas School.

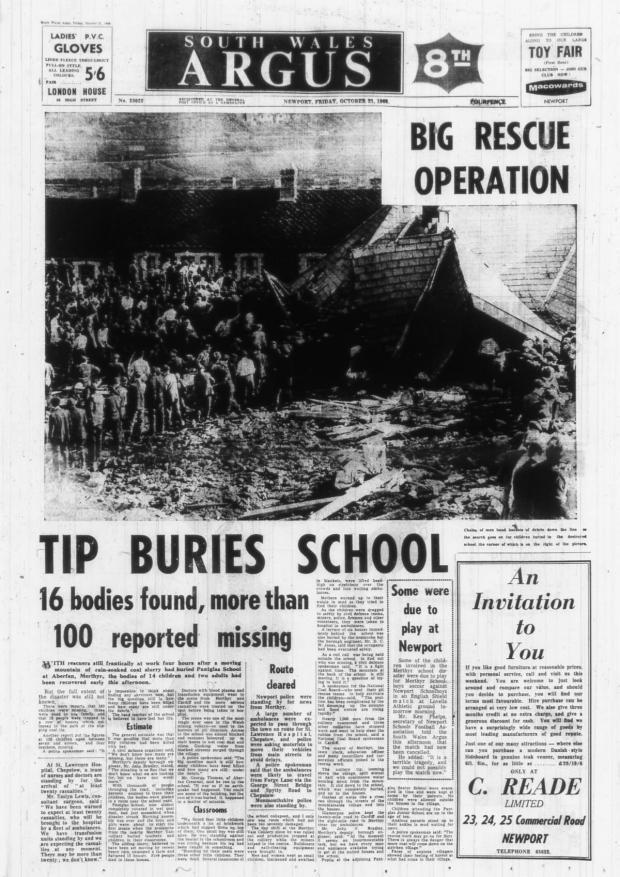

By the time later editions of the Argus came out that evening, the disaster was only hours old. We were told that the bodies of 14 children and two adults had been recovered by the "early afternoon".

It added ominously "the full extent of the disaster was still not known." By this time, a police spokesman was already saying it was "impossible" to think about finding any survivors.

One resident told how he ran to the school to help. "It was as if an earthquake had happened. You could see some of the building, but the rest of it was buried. It happened in a matter of minutes."

He said they found four little children underneath brickwork which had slipped down on top of them. One small boy was still alive. He was standing against a heater in the schoolroom and was crying because his leg had been caught in something.

There were three other children standing by their seats. They were dead.

South Wales was used to seeing the horrors of pit disasters, but it had seen nothing like this. Senghenydd, Abercarn and Abersychan and more had seen hundreds of miners perish underground. But this time, it was the miners who came to the aid of those at the surface.

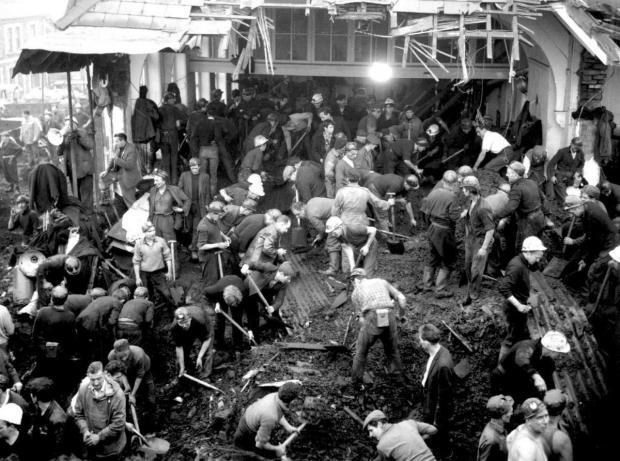

It became an abiding image of this cruel tragedy. Miners wearing their helmets, stripped to the waist and still grimy from the pits they had rushed from, digging furiously to save the children buried beneath the slurry.

Pit props and girders were brought by the National Coal Board to shore up parts of the collapsed classrooms.

By the afternoon of the Friday around 400 miners were estimated to be at the scene. Hundreds more would come to give what help they could.

Many came in late afternoon to relieve the men who had been digging through the morning.

A police officer at the scene said: "I have never in my life seen so many people work so hard together. It is a wonderful effort."

The tragedy was played out in hundreds of different ways that weekend.

We heard how the school's deputy head David Beynon was found dead holding five little children in his arms.

"They had died clutching each other" it told grimly.

Another teacher who died was Tredegar man 21-year-old John Davies had started work as a trainee at Pantglas school only weeks before the disaster.

One of those the Argus talked to was Pauline Evans.

The 27-year-old was sat on the steps of her home in Aberfan.

Exhausted, grimed in coal dust, her clothes covered in mud, she told how she had helped rescue over a dozen children.

As soon as she heard what had happened she ran to the school, and because of her small size was able to get in through a window with the help of a nurse.

Her quick actions saved many lives that day.

"When I got inside" she said, "there were about a dozen children screaming at the tops of their voices in one classroom which had only half-collapsed.

"I helped with the nurse who came inside with me to hand them through the window to safety. We found some more in another classroom and we helped them out too."

But it was not the joy at saving those lives which dominated her thoughts. She spoke instead of the one child whose life she could not save.

"We could hear the voice of a little girl but could not see her. We could not get at her because there were other children with her.

"If we moved anything everything would collapse. So we could not rescue that little girl, who said her name was Katherine. I have been thinking of her all day long."

As that desperate Friday passed in to Saturday, the work continued under lights strung up by the miners. Hope of finding anyone alive faded and the search became one for bodies.

Argus reporter Mary Burge arrived in Aberfan on Friday afternoon just as the call went out for silence.

The digging would stop, machines would be turned off, the faces of those watching etched with anguish, hoping against hope that a voice had been heard from beneath the rubble.

But, she told us, those moments were brief and they often foretold the discovery of another body.

There were reminders, even in this hellish place where men staggered knee-deep in coal slurry, of the life before the catastrophe.

A classroom away from the main building was used as a medical centre. But as hope for finding anyone else alive, it became a mortuary.

The walls carried pieces of the children's writing practice - all bold colours and capitals.

"Yesterday, last night, today, tonight and tomorrow" one read. Another: "I went, I saw, I am going."

So as the dead were found their little bodies were laid out beneath other children's cheerful drawings.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here