HEREFORDSHIRE’S celebrations of the 75th anniversary of VJ Day today (Saturday, August 15) have, like those for VE Day in May, will be muted by coronavirus restrictions.

Nevertheless, it is important that the sacrifice of those involved in the fighting in the Far East is honoured.

By far the biggest celebrations of the end of the Second World War were on VE Day, when the war in Europe came to an end.

But there was still a job to be done in the Far East, and much bitter fighting to come.

But on August 6, 1945, the Americans dropped the first nuclear bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, followed by another on Nagasaki on August 9.

RELATED NEWS: Herefordshire marks 75th anniversary of VE Day

On August 15 – which later become known as VJ Day – Japan surrendered. The Second World War was over.

In Hereford, revellers gathered in the city centre to link arms and sing patriotic songs.

The celebrations has been ignited by Prime Minister Clement Attlee’s announcement that the last of the enemies had been laid low – Japan had surrendered (Attlee had replaced Winston Churchill in July of that year).

Thunder-flashes that had been held in wait for army and Home Guard exercises became celebratory fireworks, and bedroom lights were switched on in upper storeys of homes and offices.

Bonfires were lit at Westfields and on the Lugg Meadows.

Daybreak brought a downpour of rain, but spirits were not dampened. Celebrations continued, and by late morning the sun had come out.

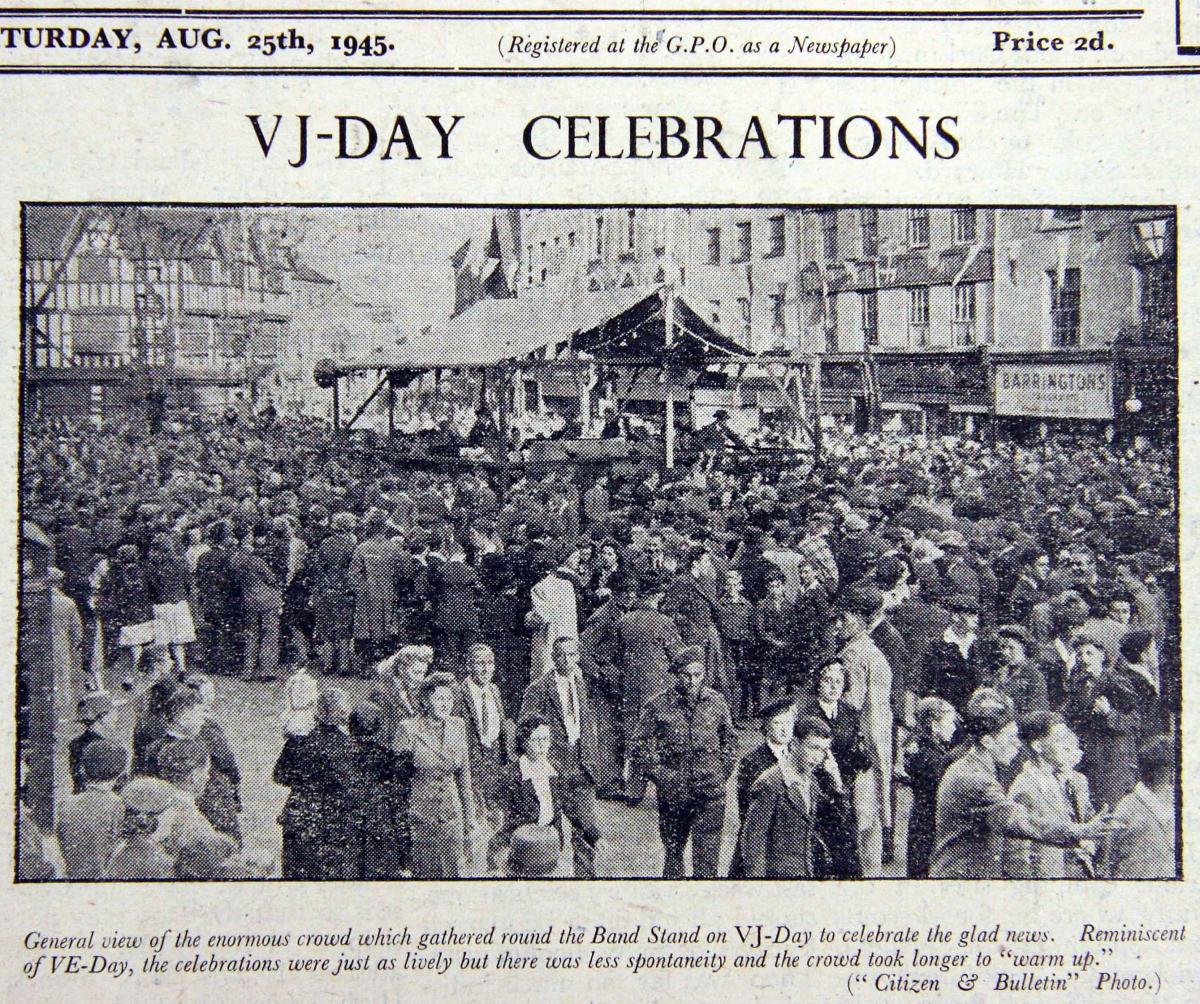

The bells of Hereford Cathedral rang out, and Hereford City Band provided music at the High Town bandstand.

Queues formed outside cinemas where many were showing a film featuring a speech by Lord Louis Mountbatten.

The pubs were packed in the evening, and soon after 8pm bartenders had to cry: “Sorry, no more beer – only whisky, sherry and port.”

By 8.30pm there was dancing in High Town to the music of Wynne Oxlade and her band with Bob Brownbridge as MC.

Speeches by the deputy mayor Alderman RC Monkley and town clerk TB Feltham were followed by a relay of the King’s message to his people.

An Australian airman then came to the microphone to laud the virtues of the British Commonwealth of nations.

Huge crowds joined in the dancing, with the Hokey Cokey and Palais Glide featuring among the favourites.

Fireworks were let off at random, and appeals for more care fell on the deaf ears of people determined to enjoy their fling.

Many people from surrounding villages poured into Ledbury for the town’s celebrations, which included a bonfire at the cattle market, dancing to loudspeaker music from Messrs Hooper’s radio shop in the High Street and bowling for a pig.

Ross-on-Wye Women’s Institute had organised its annual fete for that day, and a record crowd swarmed down to the town’s cricket ground where attractions were laid on.

The people of Monmouth heard the signal of peace courtesy of a bugler touring the town by car.

At Leominster, there was a bonfire in the Croft Street area, and some revellers paid an early-morning visit to the home of Mayor Lewis J Price.

The Leslie Preece Band entertained 400 dancers in a joyous mood at Bromyard, while at Kington there were celebrations near the Market Hall.

A large crowd gathered at the Town Clock in Hay-on-Wye, where a bonfire blazed.

The SW and S Power Co lit the council chambers and a set piece displayed a crown and royal monogram.

Pictures courtesy the Derek Foxton Archive

How VJ Day signalled the end of years of hardship at home

VJ Day meant the beginning of the end of years of hardship for civilians at home in Herefordshire. Author Helen J Simpson reflects on a childhood that was happy, despite the occasional terror of air-raids

I was just six years old and living in Hereford on that fateful early morning in July 1942.

Once again, with my sister Diana clutching our cat and my widowed mother leading our faithful old spaniel Punch, we were making our way to our makeshift air-raid shelter in our backyard fronting onto West Street.

Meanwhile, on that fateful night our two step-sisters in their late teens, Rae and Pauline, were volunteer firefighters, sleeping on makeshift camp beds on the top floor of Mac Fisheries Shop in Broad Street.

They were armed with their ARP fire buckets and inadequate hosepipes.

I remember feeling terrified that night by the noise yet again of the air-raid siren and loud explosions coming from somewhere, while we waited once again for the sound of the all-clear siren.

In the early hours a lone German Luftwaffe pilot flying low had been making his way, following the shift workers known as the Canary Girls in their red Midland Bus, to our ammunition factory at Rotherwas on the outskirts of Hereford.

I shudder to think what would have been lost if after trying to take out our ammunitions factory that morning the pilot had decided to unload yet a third bomb, focusing on our city centre – the fate that fell upon the city of Coventry...

It was before the war that my enterprising widowed mother began to expand our business, and at the back of our premises in Eign Street she built a pork pie bakery and sausage-making enterprise employing 30 people, where sausages and pies were turned out by the score to supply the local hospitals, canteens and schools.

In 1942 Hitler, after blitzing London, began his assault on our British cities – Liverpool, Birmingham and Coventry – and the RAF had made its first daylight raid on the Ruhr in Germany.

In August Churchill had begun his four-day visit to Moscow to discuss with Stalin the establishment of a second front in Europe.

Towards the end of October, the Germans had bombed Canterbury as a reprisal for the bombing of Cologne.

It was also at that moment in 1942 that the Japanese had taken over Singapore, and it was when my late husband Robert was passing out as a naval cadet at the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, along with the 55 special entry cadets, known as the Free French Navy, with one Canadian cadet who later became known as the naval historian Captain Rolfe Monteith.

There were also two Norwegian cadets – all were training ready for action.

It was the year after Prince Philip in 1940 had passed out as a naval cadet midshipman and was sent to join the reconditioned First World War battleship HMS Valiant in South Africa.

During those war years I well remember attending shows at the now vanished Kemble Theatre in Broad Street, Hereford, so famous as the home of the 17th and 18th-century thespians David Garrick and Sarah Siddons.

There were also the weekly Repertory company’s performing plays at the County Theatre on Berrington Street.

Before the advent of television, in those days in Hereford all shops closed on Thursday afternoons, and people for entertainment either strolled up Edgar Street to support Hereford United, or booked a matinee performance at the County Theatre.

Monday nights the players were never word-perfect as they were performing such newly written works as Blythe Spirit and French Without Tears, but by the Thursday matinee they were more or less word-perfect, and my sister and I very much looked forward to the Christmas pantomimes.

At times, our family's shops would often run short of meat supplies, and we relied on country folk to bring in their rabbits for sale.

We also sold large quantities of the tinned Spam, and the Libby’s tinned corned beef from South America. Our own beef dripping sold well too.

I can remember helping my mother in the school holidays, standing behind the counter, marking the government-issued weekly ration books.

We all got by with the weekly allowance of one egg a week, 4oz margarine, 2oz tea, bacon/ham 4oz, meat to the value of 1s 2d, 8oz sugar, 2-3 pints milk per week, and 12oz sweets every four weeks.

There was no such thing as obesity in those days. I firmly believe we were as a nation mostly fit and healthy.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel