A FASCINATING glimpse into the life and times of Hereford more than a century ago, when the city was lit by teams of lamplighters, has come to light with the discovery of a well-thumbed old book.

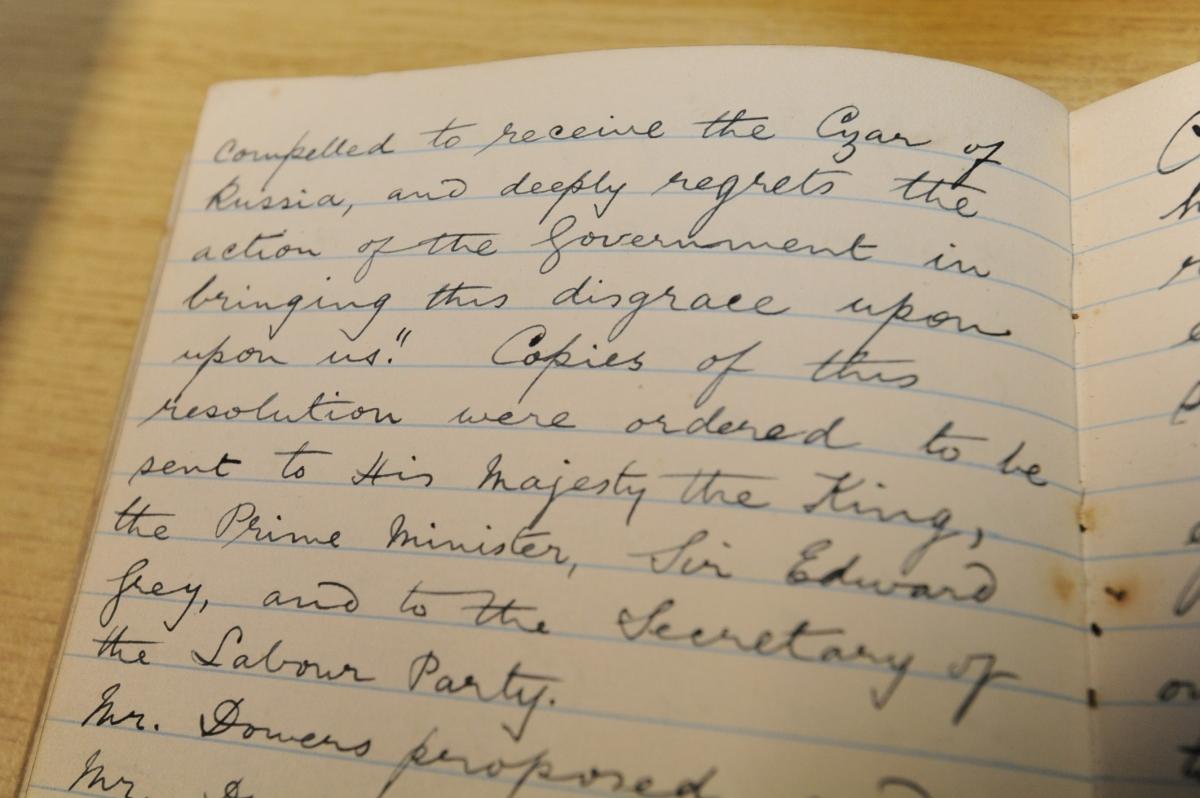

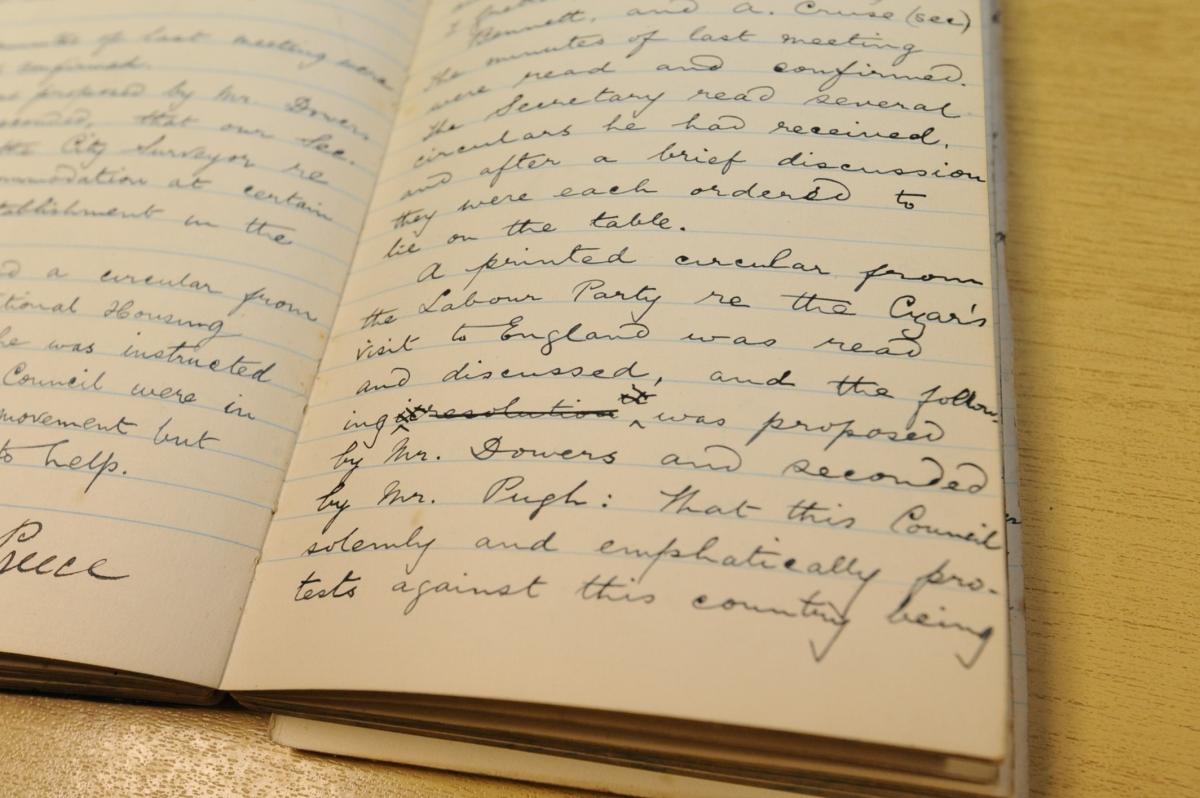

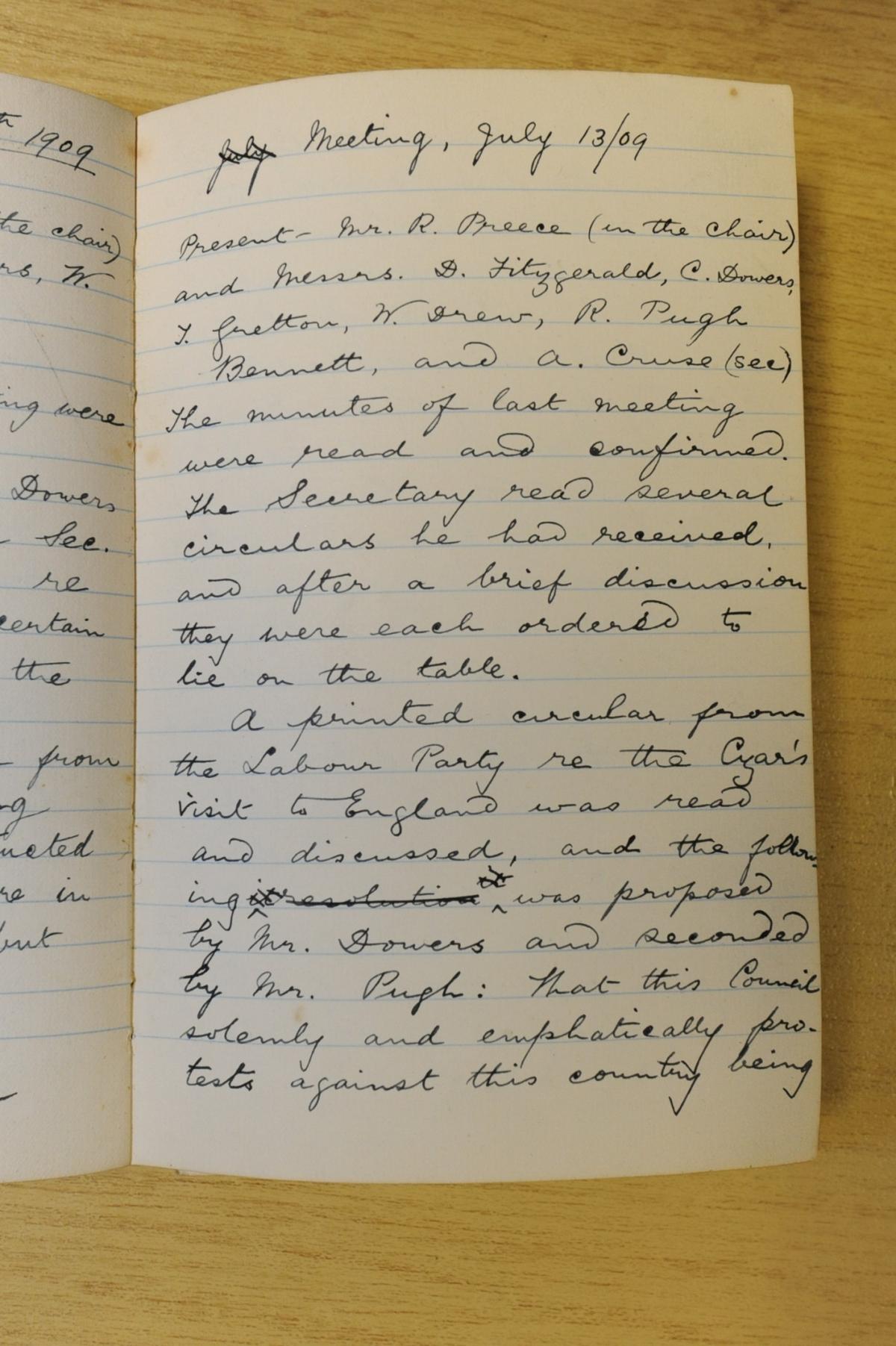

Details of daily life from 1903 up until the First World War are neatly catalogued in this record kept by a group dedicated to the welfare of the working classes.

Not unlike today's gripes, Hereford Trades Council strived to address housing shortages, soaring food prices, even potholes in the road.

Records date back to the group's first constitutional meeting in 1903 at the Golden Cross inn, Maylord Street, from which point they took up the issues of jobs, housing, health and safety.

The minute book has just been given to Kington Museum, having once been kept by the late Ruth Gates, a founder member of the co-operative society in Hereford, who eventually retired with her husband Harry to Almeley.

Back in 1904, members were demanding immediate action to remove a "death trap" in the city - they claimed that the Victoria Bridge and nearby footpath were in a dangerous state.

In the same year they pressed for"inclusion of a bath" in working men's houses, and took out a subscription for Working Women's magazine.

The welfare of lamplighters in Hereford came under scrutiny, with calls for new rulings on Sunday working. Hundreds of workers were supported by the trades' council including tailors, postmen, bricklayers, carpenters, bakers, engineers and of course corporation employees.

Murky urinals at the bottom of Commercial Road were among matters considered by the council.

"The Omnibus Yard has no place of convenience for employees," the secretary noted. Further horrors existed in St Owen's Street and the city council was pressed on Aylestone Hill's "dangerous slope". Other problems required attention: 'Cyder Works Walk' near Ryelands Street, the Old Canal footpath and an overgrown hedge along Workhouse Lane path at Greyfriars.

The tragic drowning of a boy in the River Wye aroused fury among members who had raised concerns months before. "This disaster mainly arose from the ignoring of the warning communication made by this council," the book records. While large sums were spent in the improvement of property they argued, equal expenditure was vital for "the protection of the children of the working classes".

They petitioned the Prime Minister in 1905 to grant school meals, and pressed Hereford City Council to adopt a minimum wage of 21 shillings per week. The employment of children in rural areas was a major concern, noting "low wages, ignorance and introducing child slavery with its attendant ills".

In 1912 Hereford's library committee's knuckles were rapped over refusing to have the Daily Herald in the Reading Room, and disgust at the housing committee's decision to raise rents of new municipal homes for low paid workers to three shillings and sixpence a week (35p).

During the First World War, the trades' council urged a relief committee to look after wives and families while breadwinners were away, and strongly protested against Hereford traders taking advantage of the European crisis by putting up the price of food. By 1915 members called on the mayor for a public meeting to ease the soaring costs of bread.

Further details can be seen in this little book which will be on display at Kington Museum. Opening times: Tuesdays and Thursdays 10.30am - 4pm and on Wednesdays and Saturdays 10.30am - 1pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel